It’s three in the morning in Cusco, Peru, and I am unable to sleep. My heart is pounding in triple time. My hands and feet are in a cold sweat. I am hyperventilating, and my stomach is doing somersaults.

It might be hard for an outside observer to detect why: I’m in a cozy hotel room with my wife and daughter. It’s day two of a 2-week dream vacation that will include hiking, relaxing, food, and culture.

So why do I feel like my heart is going to explode out of my chest? Because, ironically, of my need to NOT be worried. You see, for weeks we have been talking, preparing, packing, and yes, worrying about what will happen once my family arrives to the high altitude region of Peru.

We have signed up for a 5-day hike in the mountains that will eventually bring us up to a maximum of 16,000 feet (don’t people just keel over and die at that altitude?). Every expedition documentary I’ve ever seen keeps replaying through my head, the ones where they talk about people freezing to death on a mountain, how it feels like drifting off to sleep—only you never wake again.

Our travel clinic doctor, a clone of the high-pitched exorcist in the original Poltergeist movie, poured kerosene on this anxiety cocktail: “Use hand sanitizer after touching anything. Never touch an animal because if they have rabies you will die. You might want to get yellow fever and malaria treatments… totally up to you.”

And my favorite: “Some people can get a stroke when over-exerting themselves at high altitudes.”

So $500 dollars, 3 different insect repellents, 2 types of antibiotics, and one altitude sickness prescription later, I was externally prepared but absolutely terrified to start the journey.

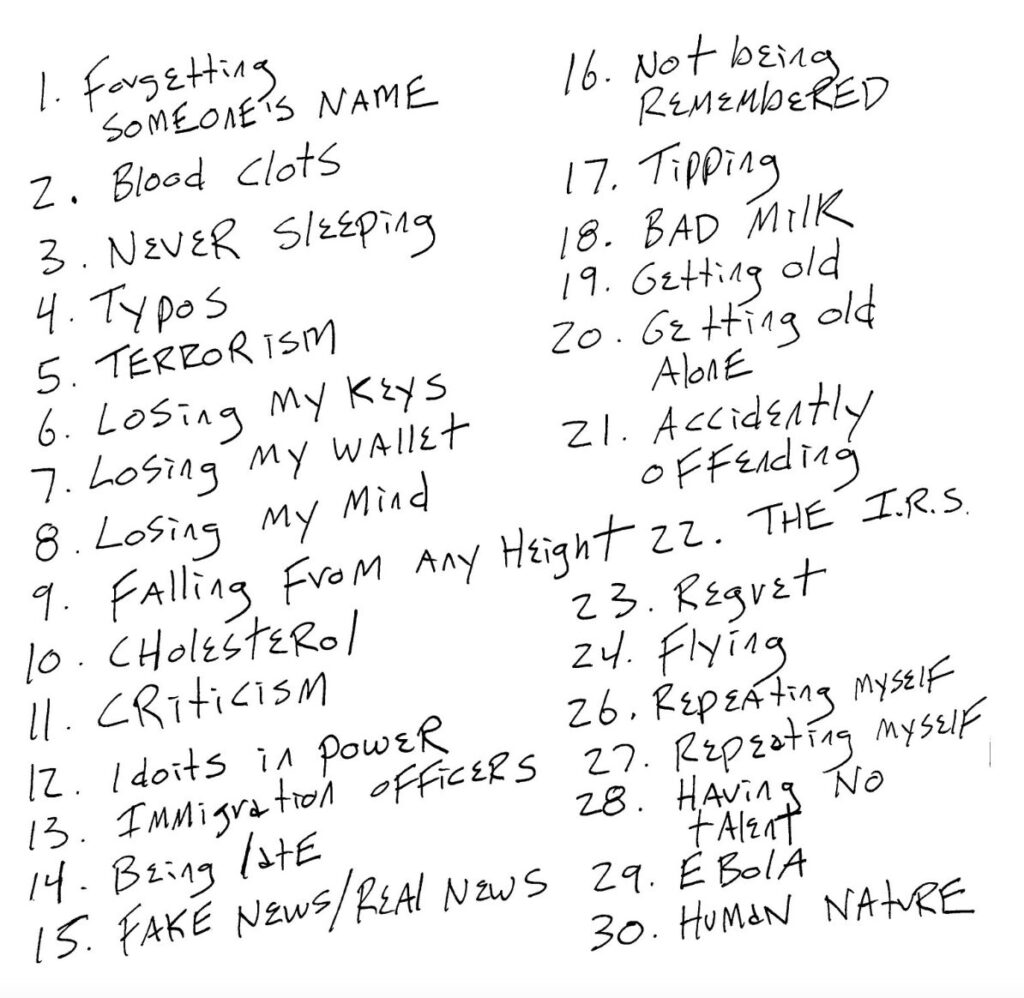

My 16-year old daughter and I were traveling alone for the first leg of the trip, and my anxiety was fueling hers. Out of desperation, we tried something I do with our clients when we’re trying to get them to step into a difficult meeting or situation: We tried to imagine every single thing we were worried could possibly go wrong. Here is our (partial) list:

At the end of our journey, we would check to see which of these things actually happened…

The day before our hike, I had been haunted by the voice of the ferret-like travel doctor: “Altitude sickness can be very serious.” So, at dinner, to calm myself, I took a Diamox, which is supposed to quell altitude sickness and prevent your eyes from popping out. My son informed me that I was only supposed to take half a pill, not the whole thing I had just swallowed. The effect of my double dose was that middle-of-the-night Cusco panic attack on the eve of our 50-mile, 16,000 foot hike. That’s half the height of a plane’s cruising altitude! The very thing I had taken to calm myself had cranked up my worry to an 11.

I lay there in the dark, certain that my lack of sleep meant that items 1-5 on my worry list were now guarantees, and we hadn’t even set out yet.

Here’s what happened: The hike was hard. The only way to get through it was to focus on one step, one breath at a time. The moment I looked up to see the series of switchbacks that lay ahead, my will and morale would falter. When I stayed with what I was doing in the moment, I found a tempo and calmness that got us to the top of Salkentay Pass at 16,000 ft.

After the trip, my daughter and I went over our worry list to see what came true:

#1 Sleeping poorly -Only that first night in Cusco. (Thanks, Diamox!)

#11 Panic from sensory overload – Only in Vegas during the layover

#14 Lost luggage – Between Vegas and home. Delivered the next day. No big deal.

Nothing else on the list came to fruition! All those hours planning and worrying, and we returned with nothing to show for ourselves but a couple minor inconveniences, some unused oxygen canisters and enough assorted medicines to save the Incas at the height of their reign.

I worry a lot. I worry about my work, my health, my kids. I spend tons of time worrying. But why? It seems like what I need to be doing instead is trusting. Trusting that if something crappy/unexpected/surprising happens I will figure it out. Trusting that being relentlessly present is a better way to live then being constantly worried. You’d think by now I would have figured this out, but I’m still learning.

I’m going to keep making worry lists. They seem helpful and not just for trips. I’ll scribble them down for my next presentation, performance, exhibition, important conversation. Give it a try as well. After it’s all over, go back to see what really happened. My hope for us both is that the lists will be mostly unrealized and that, over time, this practice will help us let go of advance worry and deal with the reality that meets us in the moment.