t’s 1977. I’m in sixth grade and I’m in trouble.

Mrs. White, my sixth grade teacher, has just asked me to stay in from recess, which secretly is great because it’s February in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and recess consists of small cliques huddled for warmth near the frozen kick-ball field, talking about the latest episode of The Six Million Dollar Man.

Mrs. White (who, fittingly, has a bob of short white hair) has a permanent scowl plastered on her face. She approaches my desk in the now-empty classroom holding my science notebook. Earth Science: mantel, crust, tectonic plates, all the good Earth stuff.

“What are these?” she asks, as she places the book down in front of me and, like a magician, turns the pages while never breaking eye contact with my guilt-ridden face. I am terrified to look down for fear of discovering that something awful has been found between the pages of the notebook: a dead pet, swear words, some body fluid I forgot about. But I break eye-contact with her long enough to glance down and see, to my surprise, nothing unusual. No porn. No snot. It’s just my notebook.

But her now-intensified scowl tells me I missed something. And like a moron from a bad high school movie, I blurt out “What?”

Mrs. White’s stare remains fixed on me, but like she has a second pair of eyes somewhere, she keeps flicking through the pages, one after the other, looking like they always do, filled with notes (a few) and doodles (a lot).

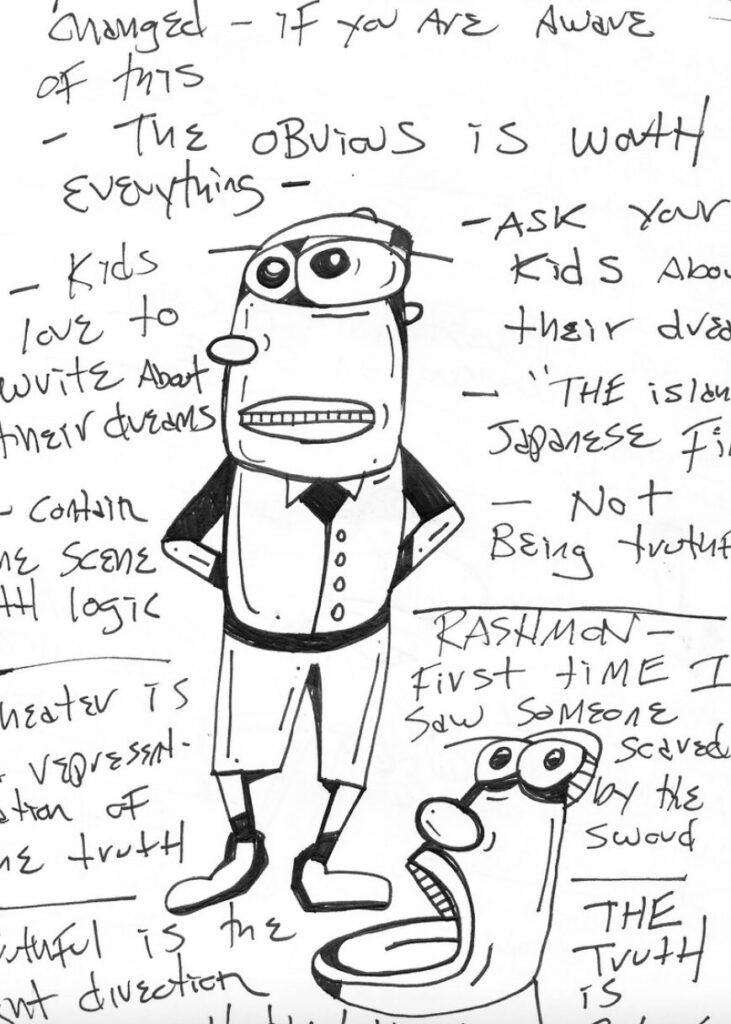

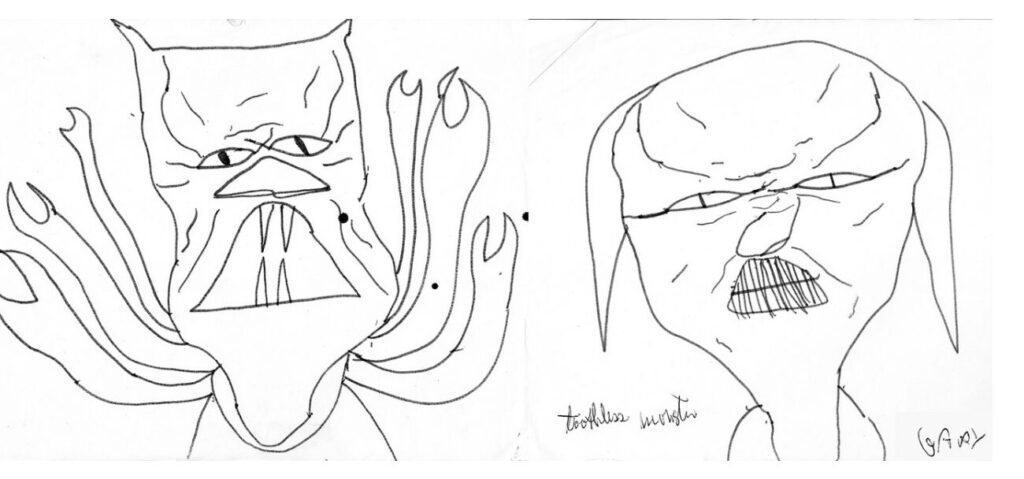

“What are these?” she repeats and, like a sorcerer, jabs her finger at a cartoon that I created during the last lecture on the Earth’s molten core. It depicts a cat with wide eyes looking up at a giant’s foot that is coming down towards it, spelling immediate kitty doom. My notebook is filled with these- mock ground attacks, space ships, helmeted troops, monsters locked in aerial combat, etc.

And these doodles are not a one-time Earth-Science thing. They are everywhere, in all my notebooks, my textbooks, sometimes on my hands and arms. I am addicted to doodling.

Mrs. White is pissed. She is paid professional who works hard to come up with detailed lesson plans about Pangea, and here is a disrespectful twelve-year-old who is blatantly ignoring her, and instead re-creating Battle Star Galactica (original series) in the margins.

“Are you even listening at all in class?” she bellows.

Of course I am. I know the difference between igneous and sedimentary rock. But as soon as I have a pen in my hand and the drone of her monotone voice begins, I am compelled to scribble. I just can’t help it.

I want to tell her that it’s just something I have to do. That she shouldn’t worry because I am still learning stuff. But I am paralyzed by her stare and intensified scowl. So I look up and say…nothing.

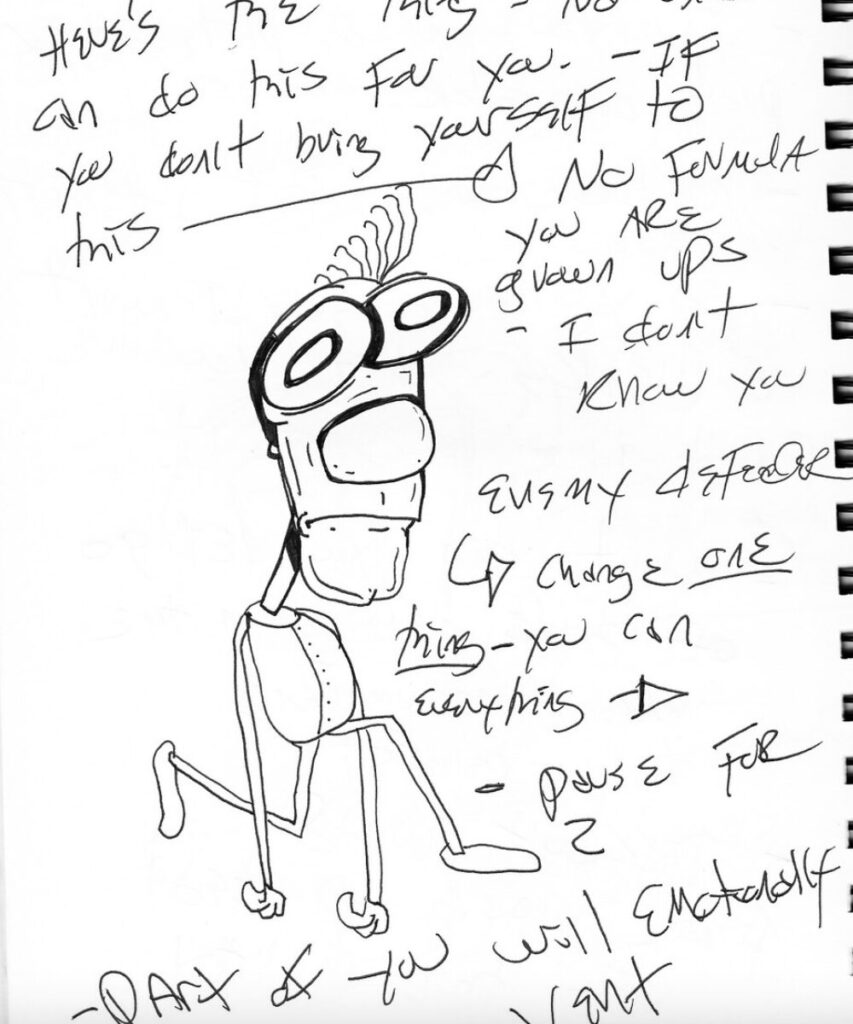

Now it is 2016, and I’m sorry Mrs. White; I never stopped doodling. I still have notebooks, and I go to meetings with important people who work at big important companies, and I doodle. But now I am shame-free and transparent with my scribbling because what I have learned since that frigid day back in 1977 is that doodling helps me listen.

I didn’t need articles from Time, NPR, Nova and others to tell me this (although it helps). It’s simply that this unconscious habit has served me throughout the years.

When I am doodling I am at a heightened (but relaxed) state of being present. I can remember almost everything that has been said. I can easily pick-up on the emotional states around me. It’s like I have acquired some new set of listening superpowers, the ones that remind me most of the way I feel when I’m in the zone on stage with fellow improvisers.

Design consultant and creative guru Sunni Brown says, “The doodle has never been the nemesis of intellectual thought. In reality it’s one of its greatest allies.” And Mrs. White, here’s a quote for you from a Nova Learning article on the power of scribbling: “Doodling should not be flatly discouraged, but rather looked upon as on potential avenue for real growth as educators deduce the best methods for helping students to learn and the vital skills they will need for success in the future.”

Postscript

A few months after being chastised by Mrs. White I found myself outside at recess in the midst of a frenzied snowball fight. During one intense barrage, I let a particularly dense snowball fly towards my rivals. I completely overthrew the ball and watched it (as if in slow motion) as it descended directly on to the back of Mrs. White’s white head. I immediately ducked behind the metal encased electrical box that our team was using a cover, leaving my best friend Tom Brooks standing there to be falsely accused of hitting our sixth grade teacher on the head with a snowball. Tom was banned from recess for a week. I have never confessed to this injustice, until now. Sorry Tom. Sorry Mrs. White.

(below, doodles from my most recent notebook)